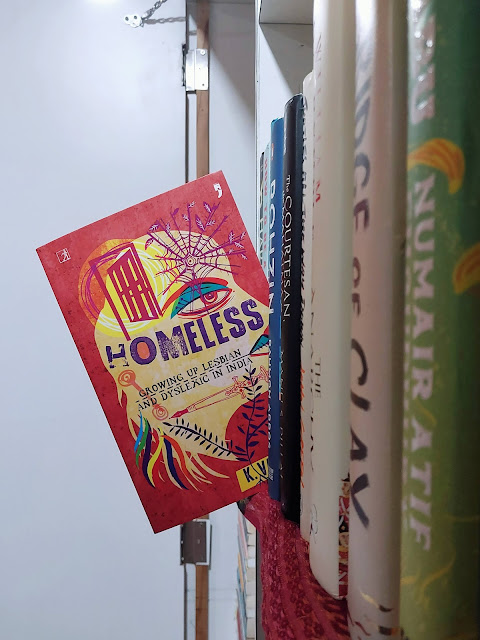

Homeless by K. Vaishali is a memoir of the author’s days spent introspecting in her own company as she is forced to leave her Mumbai home after coming out to her mother as lesbian; at first, in a co-rented flat in Ahmedabad and then in a UoH hostel, left to fend for herself devoid of the comforts, yet burdened with the ongoing challenges of dyslexia and dysgraphia. The memoir, for the major part, revolves around this major conflict—a type of parenting, the end goal of which is to prepare children for marriage and reproduction, or simply, to affirm that their children are as capable and qualified as children of other community members. Exactly, it doesn’t make sense to our generation. Parenting is and should be about embracing and celebrating children’s individuality while nurturing their physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual needs to help them navigate the turbulent waters and positively impact the world.

When K. Vaishali scores below average in an exam, she gets physically abused, and whacks on her head and pinching on her thigh continue as dyslexia remains undiscovered until much later. The problem with such type of parenting is the unacknowledged generational gap that leads to the normalisation of the imposition of parents’ beliefs, ideals, perceptions, and everything imaginable—that it’s okay to make your kids go through what they had gone through, that it’s maybe good for developing their kids’ mental strength, that whether it’s parental abuse or frequent fights between parents, there are going to be no repercussions. Ultimately, the children may suffer from clinical depression and lifelong mental disorders like anxiety and OCD. If left unattended or found no conscious way to deal with it, the next generation is fated to receive what is popularly known as “generational trauma”— a deeply ingrained legacy of pain and suffering, including substance abuse, violent behaviour, and whatnot.

Before I digress further from the memoir, apart from the subject discussed above (one of the several issues that surface in the book), the author talks about being lonely, breakup, finding a partner, the fear of getting outed as having ‘homosexual tendencies’ in the times when homosexuality used be a criminal offense, casual homophobia, and daily struggles that come with many disorders she is trying to control and manage consciously. Although this is a gripping memoir with a seamless flow taking you through the roots of problems and back to anecdotes, the narrative felt excessively one-dimensional, with a microscopic focus on inconveniences coupled with dark humour, making it less of a memoir and more of a trauma dumping that could be dealt with a multifaceted or multi-layered approach, something that I’m expecting from the author’s upcoming novels, for which, she has shared fascinating ideas throughout the memoir—a box full of kimberlites, where a shining gem is waiting to be discovered, cut, and polished. Overall, as the synopsis reads, living with disabilities that are not apparent from the outside, fighting against homophobia, and being a victim of inter-generational trauma are the truths of many young Indians, and we must listen to them.